How Daring Leadership fosters Feedback Culture

Ever since I watched Brené Brown’s famous TedTalk about the power of vulnerability, she has been a source of inspiration to me. Dr. Brown is a social researcher and author who’s widely known for her groundbreaking research on shame and vulnerability. Recently I read her bestselling book “Dare to Lead” in which she examines what it means to be a brave leader and how tough conversations promote trust at the workplace. Let me share some of her insights as well as a great tool to give better critical feedback.

The Value of Daring Leadership

“Dare to Lead” is the result of more than two decades of Dr. Browns research and leadership work with major companies. It’s a collection of actionable learnings gained from 150 interviews with C-level executives. For her research, Dr. Brown used a grounded theory approach in which the data collection and analysis happen simultaneously. Rather than formulating a hypothesis beforehand, the theory emerges over time and is grounded in data.

During the interviews the executives independently stated that in order to be successful in our ever-changing world, leaders have to become braver and cultures more courageous. While they agreed on the need for what Dr. Brown calls “daring leadership”, the answers as to how to achieve it varied widely.

Instead of looking for a common denominator in their answers, a better question to ask is what stands in the way of becoming a brave leader. The answer is both simple and incredibly difficult: vulnerability.

«Vulnerability is the emotion we experience during times of uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure. […] It’s having the courage to show up when you can’t control the outcome.»Brené Brown, Dare to Lead

Being vulnerable means laying down the armour that we carry around to protect our egos - things like perfectionism, emotional detachment or cynicism to name just a few. Vulnerability demands taking responsibility for our own behaviour and holding others accountable for theirs. It means having tough conversations in spite of being afraid to say the wrong thing or get our own feelings hurt.

The Marble Jar

The underlying problem with vulnerability is not the fear of getting hurt but how we respond to that fear. Every emotion sends us an important message about what’s going on in our surroundings. Fear points towards uncertain and potentially dangerous situations — someone hurting our feelings when we’re being vulnerable for example.

So, if it’s both uncomfortable and potentially dangerous, why should we ever be vulnerable? Because vulnerability is the best tool we have to connect with others and build trust.

Trust is not built by big gestures but in small moments of turning towards, listening to and caring about each other. Every act of kindness is like putting a marble in a jar. The more marbles we collect, the more we trust a person. While trust is built one marble at a time, every disappointment, hurtful comment or turning away takes out a handful.

Thus, in order to create a trusting work environment we mustn’t turn away when things get hard or uncomfortable. On the contrary, those are the best opportunities to build trust. So instead of reacting automatically to our fear by turning away, we have to learn to sit with it, let it pass through us and then act with purpose. The good news is that even the most uncomfortable emotions only last about 90 seconds in the body. Afterwards it’s up to us how we respond, as brain researcher Jill Bolte Taylor points out:

«When a person has a reaction to something in their environment, there's a 90 second chemical process that happens in the body; after that, any remaining emotional response is just the person choosing to stay in that emotional loop.»Jill Bolte Taylor, My Stroke of Insight

The Big Shift

As the neuroscientist Antonio Damasio puts it: “We are not necessarily thinking machines. We are feeling machines that think.” A lot of people have never learned how to manage their emotions let alone put them into words. This leads to a lot of missing or misleading information when we find ourselves in a conflict situation.

Let’s take the following example: A colleague of mine repeatedly hasn’t met the deadline for a task we agreed upon. I want to address the issue and give them critical feedback.

Now, I don’t know their side of the story. One approach would be to make up a story in my mind about why they behaved the way they did. Depending on my emotional state that story will probably not be in my colleague’s favour.

But there’s another approach we can take: instead of filling in the gaps ourselves, we can get curious. A shift has to take place from “my version of the story is the right one” to “everyone’s story is equally valuable”.

The important thing is not to be right but to get it right. Before I make any assumptions, I will ask my colleague to tell me their point of view. I can ask: Why did you behave the way you did? How did that situation make you feel? What needs to change in order to resolve the issue? How does support from me look like?

The more information I have, the better I can understand their point of view and form an accurate account of what happened. Now that they’ve opened up to me, I act in kind and tell them my side of the story. This opening up to each other is where trust is built. And a solid foundation of trust is essential when it comes to critical feedback.

Developing a Feedback Culture

While we often value each others work at smartive with positive feedback, our critical feedback skills were in need of polishing. In a recent workshop moderated by Die Copiloten we got some great tools for giving and receiving better critical feedback. Let’s go back to the example from above and look at one of the tools in more detail.

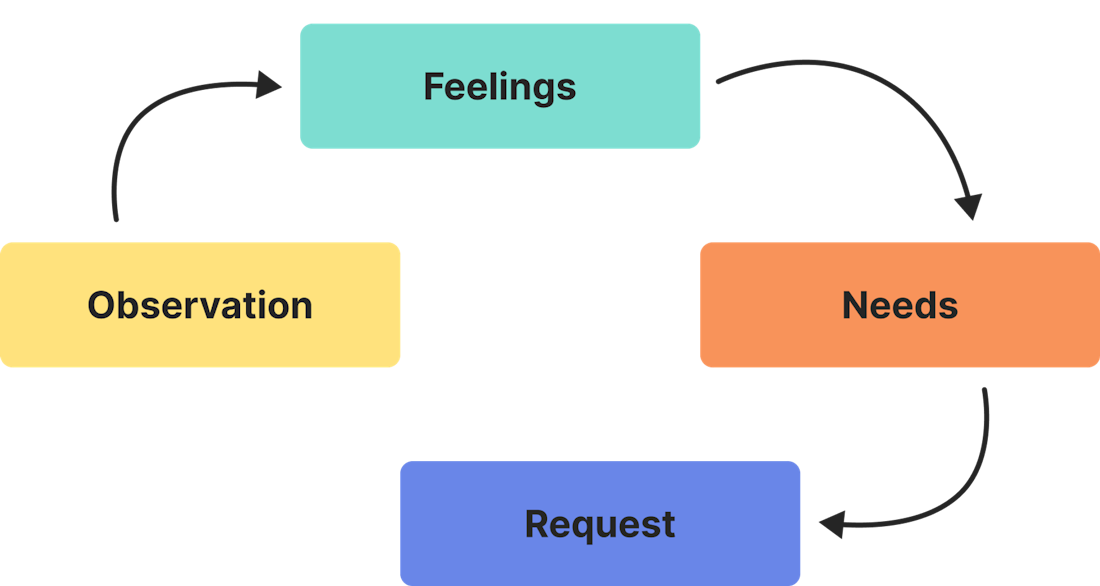

“Nonviolent feedback” is based on Marshall Rosenberg’s principles of nonviolent communication. The following four steps help to deliver criticism in a compassionate rather than a hurtful way.

1. Observation: Describe in a non-judgemental way what you observed

“We discussed the task and agreed on the deadline. You said that you were able to finish it in time. I offered to take work off your plate which you refused. In the end you couldn’t meet the deadline.”

2. Feelings: Tell the other person which emotions were provoked in you

“At first, I was surprised that you refused my help when I offered it. Then it made me angry that you didn’t ask me for help when you realised you weren’t able to finish in time.”

3. Needs: Explain which underlying needs led to those emotions

“I care about everyone feeling comfortable with their workload. I’d like you to see me as a trusted supporter.”

4. Request: Formulate a specific request

“I’d like to discuss with you how we can better handle the situation the next time it comes up. Please know that you can always approach me if I can support you in any way.”

Seize the Opportunity

According to Dr. Brown’s research vulnerability is the key to becoming daring leaders. If we allow ourselves to bring our whole humanity to the table, we invite others to do the same.

At smartive all of us are leaders in their own right. Everyone is responsible for their own personal development but also for recognising and fostering potential in their colleagues. In order to become more daring leaders ourselves, we do our best to approach uncomfortable conversations with curiosity and compassion.

Let’s not miss out on those great opportunities to build trust and strengthen our relationships. Sometimes it’s messy and sometimes even the best intentions are not enough. But every time we turn towards each other instead of away, we move a little closer. All it takes is for you to do the first step.

Geschrieben von

Nadia Posch